‘Deface’: to damage the appearance of something especially by drawing or writing on it. «It was given to me by friends long time ago from painting graffiti in the early days», says Dean Stockton alias, D*Face (London, 1978) regarding his name. «I was painting characters, faces… That became ‘these-faces’, which sounded like D-faces. I like the game of the faces and defacing something at the same time».

In the early days, more than 20 years ago now, when Street Art wasn’t even called Street Art, D*Face was posting paste-ups and bombing London streets with his stickers, stencils and his recognizable D*Dog logo. After taking over London, he soon took over the American West Coast, exchanging stickers via post with Shepard Fairey and eventually going on to have the rest of the artistic scene under his feet. By 2006 he had staged his first solo show in London, which was a sellout success.

D*Face latest move was made right in the heart of Madrid: a 20-meter high wall commissioned by Urvanity Art. We catch up on a call to get to know a bit more about his work, his past, how is he living these quarantine days and what’s to come for him.

How were your beginnings into the street culture?

Originally I was into the very early hip hop and breakdancing culture that I was fed in the UK. That was synonymous with New York and graffiti, they were hand in hand. A few years later I started skateboarding and a few of the guys I joined were all set in graffiti. I was never very good at graffiti, talking about it in the traditional sense, so it didn’t really stick with me. Skateboarding did though, so through that was when I became familiar with Thrasher Magazine and these old graphics. I started doing more punk music rather than hip hop culture. My older sister took me to see The Cramps, The Pistols… By that time you had to make a choice of whether you were into hip hop or into punk. It was kind of a weird time, you needed stay quiet about your ‘indulgences’- I stilled liked hip hop but visually I was more into punk aesthetic than anything else.

How did London play a role in the development of your work back in the day? With what other artists where you sharing the street with?

At the time there was only a hand full of people doing anything close. There wasn’t really a “scene”, I didn’t really understand what I was doing, I was just trying to use the street as a form of expression and a place to put my work – just as I am doing now. Predominantly at that time there were a few artists like, Solo One, The Toasters, Pref, The Shepherds, Banksy… A few of my friends, PMH or Mysterious Al, but it was pretty much on my own. I was really quite happy and it kind of made more sense for me and my work.

You studied photography for a couple of years and after leaving that path you started doing animation and graphic design.

I really enjoyed and still do enjoy photography but I was not going to be a world class photographer by any stretch of the imagination. I was too busy smoking weed, chasing girls, trying to be cool rather than being a very good professional photographer. My parents had given up on me at this point, my mom told me I had to get a job and my dad was more like ‘you should have gotten a job when you were 15, you’re wasting your life’. But I was determined to not get a job and my focus was definitely not working. I finally applied to study animation: that was the first time that I really solidified on what I knew I was into – I finally understood what I liked and that led me down an important path career wise. It was the first time I felt I was committed to something.

During all that time you never left the streets aside?

I was always doing stuff in the street. I was fascinated with using the public domain to express myself. That comes from skateboarding, a very honest way of using the environment to your gain, to your main self-expression. I wasn’t really going out with spray paint in the traditional sense, I was more into trying to develop a dialogue with the public so that they would understand and appreciate more a tag on a wall or a letter piece, which I love and have always loved, but I realized that gets lost on a large majority of the public.

How did you express yourself in the streets then?

Pasting, stencils, stickers… We now call it Street Art now but earlier we didn’t really have a term. It was like “us people”, my friends who were into graffiti and still are… It was I guess only a couple of years after these early years when it started to become known as something else. Most graffiti writers were still doing their own stickers at that time and there was no shame in the idea of being labelled a ‘street artist’. Now I feel like if you’re a graffiti writer, Street Art is like the most toy thing going on, so people try to distance themselves.

Dublin Dog, 2013

And you came across Shepard Fairey work visiting the U.S.

I was in New York for a college trip and whilst I’m out it always put my stickers up. I began to sees these weird little faces appearing with the Obey sign everywhere and I tried to track down who this person was. Somehow I finally come across this website that was Shepard Fairey’s and I emailed him, he was probably one of the first people I ever emailed. I told him I was doing something similar in London and if he wanted to send me some stickers and whilst I’m out putting mine up, I’ll put up his too. We started to send stickers back and forth, I sent him a bunch of posters and stuff, D*Dog faces, it was just an exchange of ideas and creativity there was nothing more to it than that. Then in 1999 he came to London for a print exhibition in a place called the Horse Hospital. That was the first time I met him.

When did opening up your own gallery comes into the equation?

In 2001-2002 I was traveling quite a lot through Europe, putting up posters and meeting other people. I went to Barcelona a lot and every other artist I knew were either doing graffiti or what was then becoming Street Art. They were also painting canvases and trying to support themselves, but there wasn’t really anywhere to show their work apart from clothing stores. I felt we needed a proper exhibition space, it should be taken seriously after all. I kept waiting for someone to open a gallery… and it just wasn’t happening.

So you managed to do it yourself?

Somebody gave me the opportunity to use an empty building they had. It was 2004 and I had no desire to be a gallerist or a curator but I felt very passionate about this movement. I took a year out basically – I wasn’t able to produce my own work during that year. I had to do everything: from organizing the show and hanging the pieces, to trying to sell the artwork, even serving the beers during the opening! It was a year of complete headfuck to be fair. That gallery at the time was called Outside Institute and it was amazing. We had some great shows, we did incredible things. But it didn’t really sustain itself and by the end of the year the person who gave me the space said I needed to pay rent for it. That was in no way feasible then, so we closed it down. But six months later I was on it again, I thought I needed to give this another try but in a different area of London. I decided to apply all that I’ve learned about ‘how not to run a business’ and ‘how not to run a gallery’ and move forward. I opened StolenSpace Gallery in 2005 and we did a couple of pop-up exhibitions before opening the permanent space.

What did Stolen Space mean to you?

It was a place where everybody could hang out together, exhibit, share ideas and form a bond over the movement that we were all part of. For me it was really just a place to fill the blank space to get artists to exhibit. That was all I thought of, I didn’t have any grand vision of anything more than that. StolenSpace is now 15 years old, and still I’m involved in the curation, the direction and whole running of the gallery.

How has your work evolved during these years?

In my older work there was more of a critique of consumerism, to the idea of the more you surround yourself with doesn’t mean you’re feeling happier or better. There was never meant to be a preach like ‘don’t drink Coke’ or ‘don’t wear Nike’. You can’t really live that life – I like drinking Coca Cola, I wear Nike and I wear brands… The message was more about recognizing the impact and effect that you may have as an individual and if there is no alternative then to go look for it. And again I think that is more relevant now that it was when I was doing it 10 years ago. We’re kind of seeing this effect more and more in our society.

What worries you nowadays?

The end of civilization, I guess is a bigger worry that anything. Trying to regain some former normality, inject it back into our lives. The impact that this has on relationships, the way we relate… in humanity I think this is very apparent. All of those things and basically all of the same things I’ve always been concerned about – it’s always been about people, relationships… I paint people that may appear to be dead but they’re not necessarily dead. They’re maybe representing a missing gap, it doesn’t have to be physical it can be metaphorical. But it’s about emotions, it’s universal.

Where do you see yourself going next?

I’ve always been fascinated with the 2D and try to go pushing to 3D… But then I get drawn back to loving the simple graphics. Working three dimensionally has always been very intriguing to me. The more murals that I paint the more I’m interested in making permanent public sculpture. For me that would be the logical evolution for Public Art and the direction I’d like to pursue.

What is it that traps you about Public Art?

You’re interacting with everybody. There is not a class, not a race, and there is not a sex. You get to interact with all these people. Now I get the amazing opportunity of painting 7-story, 20-story murals and when I come down form the mural and talk to the public it’s their reaction and what they have to say that is the most inspirational part of it to me. Bringing more people into art, making it more inclusive and less exclusive.

Size matters?

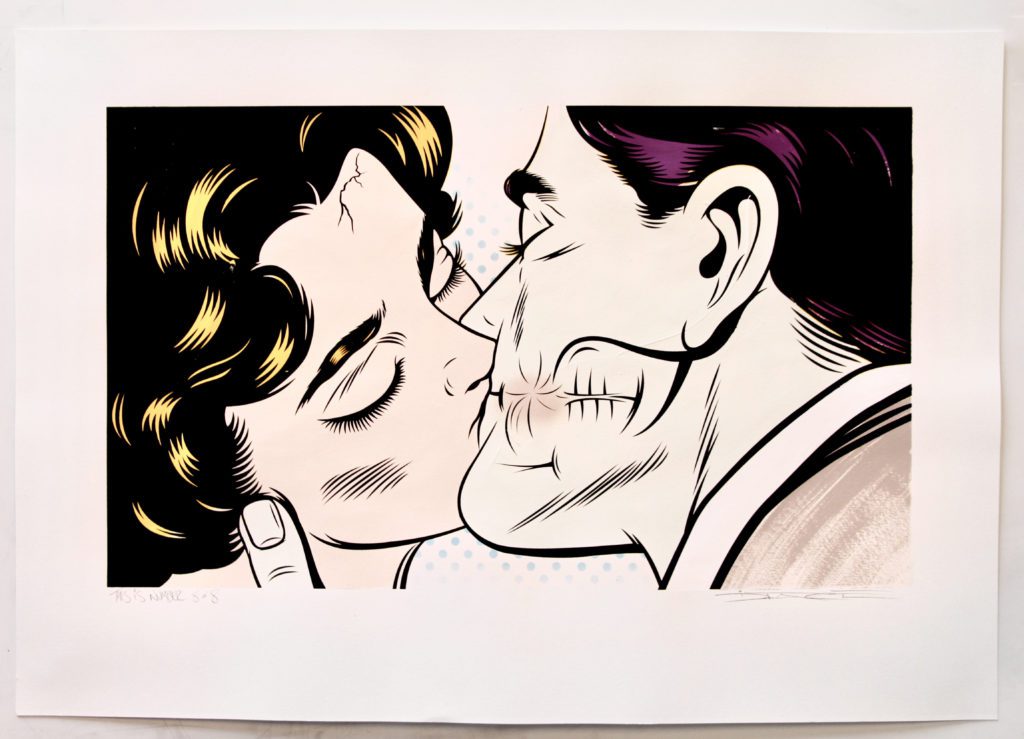

I think it’s more about if that wall is appropriate for that idea, if that is the right location for what you’re painting. Sometimes you can get much more reaction out of smaller walls that you can from huge one. My favorite wall is ‘Suck Face’ that I painted in Miami during Basel 2014 at a Middle School. The wall, the location… It was such a cool project.

Can you tell us a little bit about Madrid’s latest wall?

The wall is called, ‘Runaway’ and it’s got a play on words in terms of the paint being drippy. The guy is disappearing and running away from problems, from a relationship. That’s an artistic, graphic play on a situation, on a feeling. Is part of a new series of work. The next body of work is about deterioration, things being eroded, decayed and there’s lots of different ways in which that happens. I’m now looking at it and exploring the different ways in which something can and cannot be there.

How do you get to deal with the double identity that you get out of being an artist or street artist, and a recognized public figure?

I never tried to become any sort of street artist or even just artist. For me the most irrelevant thing is how I look and who I am, in terms of the work I produce – I’ve no desire to be recognized. I do find it quite disturbing when I see people paying more attention to who they are as a public personality, instead of the work they’re producing. If you really want to be a rockstar then it’s not about art, it’s kind of sad to see, but each to their own, you know?

Your last solo exhibition was in Tokyo during October 2019 and you presented a body of work under the name, ‘Social DIScontent’.

For me that exhibition was a question of what’s happening to our minds in our desire for information. Naturally, I hadn’t foreseen the current virus situation and the fact that now we’ve become even more reliant upon social media. In isolation phones are our window to the world so it’s kind of a scary time. I was actually looking forward to spending less time on my phone, and I find myself in a place where I’m spending even more. I’ve got two kids and I see them addicted to TikTok (laughs) and I don’t even understand it, I just think it’s crazy what they’re looking at, and what they’re replicating. I just ask myself, “where will this all take us in the future?”

What are you doing these quarantine days to avoid using your phone?

I’m trying to read books, more than I’ve ever tried to read books before (laughs). I’m trying not to pick up my phone and I still look at it every five minutes for no reason. I’m trying to leave it at home if I go to walk the dog. Just trying to take a break from it but it’s hard you know? Also, I have a studio at home so I’m fortunate that I’m able to continue working. These days I’m mainly on the computer trying to get on top of things that I wanted to do and haven’t found the time before.

What’s coming next for D*Face?

I was meant to be having an exhibition in Taipei, Taiwan, in May so I’m still working on that exhibition. Although it’s very unlikely that the show is going to happen on schedule, given the current situation. But it’s still in my mind, is a good focus to produce work for that. Actually, the next thing for me is that I don’t really know what is next.